Git Is Your Friend not a Foe v4: Rebasing

This time I’ll talk about more complex things, which give developers more power over their life. Actually, they just look complex. In fact these are quite natural operations over Git commit history structure, which was described already in my previous posts and gazillions of posts by other people.

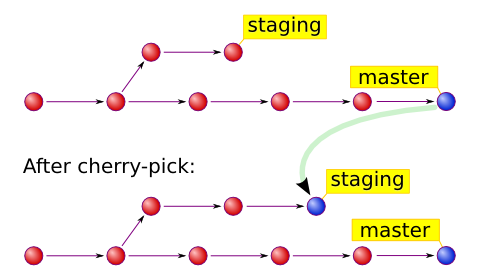

So, let’s start with the simplest. Mr. Cleverhead sometimes fails to remember

which branch he is currently on. He commits to a branch master, while in fact

he should have committed that to staging. What can he do to fix it? He

decides to run git show, save the commit as a patch, then checkout branch

staging, apply patch there and commit with the same commit message. Well, it

happens so that Git already has a command that does exactly this automatically!

It is called git cherry-pick. Besides fixing Mr. Cleverhead’s reputation, it

is also quite often used for example to backport commits to release branches.

Note, however, that this still requires Mr. Cleverhead to remove his commit from master. We believe in him.

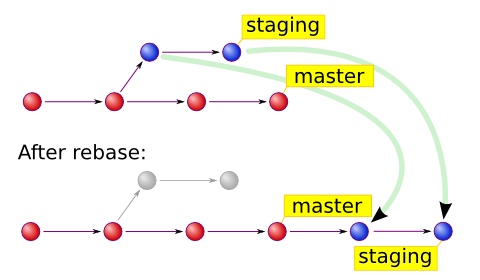

The next big complex thing is a branch-wise cherry-pick. This is called a

rebase and often casts a great deal of confusion upon novice Git users. But

actually rebase is to cherry-pick as is multiplication to addition: by doing

rebase you just cherry-pick a series of commits on another branch. Although

git-rebase manual page is ugly and unfriendly, it tells the same basic thing:

rebase is a series of cherry-picks, followed by a branch reset.

Note the desaturated old commits. Despite Git changed the branch head, it didn’t remove these old commits. They are still accessible through reflog, or by their SHA1 ids, in case you realise you’ve made a mistake.

There are many use-cases for git rebase, from Mr. Cleverhead committing

several commits in a row to a wrong branch, to complex integration and release

cycle management workflows. See, for example, http://nvie.com/git-model .

There is also an interactive mode for git rebase. And it is truly awesome!

It allows you to edit your branch in any way you want: remove commits, edit

commits, squash commits, even change commit order. So try it out. Now.

The post would be incomplete if I didn’t mention git filter-branch. It is

basically the same as rebase, but it usually affects the whole branch up to the

initial commit and for every commit Git performs a certain action. It is very

complex and powerful tool that is quite rarely needed and quite more rarely

used. Its uses include: removing a file from the whole project history (for

example because of license issues, or because Mr. Cleverhead accidentally

added his grandmother’s recipe book five years ago); fixing author’s name in

commit messages; creating a separate Git repository from a subdirectory. All

this comes free with Git and doesn’t require you to spend weeks doing this any

other clumsy way.

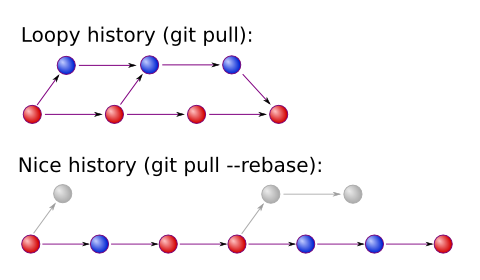

Last thing I would like to mention today is pull-rebasing. This refers to the

following problem: by default git pull means git fetch followed by git

merge, which is perfectly fine if you haven’t committed anything locally. But

if you have, this creates a merge commit. This is perfectly fine either. But if

you do small commits often, or work on a big feature in your branch and merge

master often to be in sync with updates, this will create a so-called “loopy

history”, which usually pisses people off. Especially Linus. So if you have

committed a small fix that you can’t push because Mrs. Slowrunner managed to

push a commit before you, use git pull --rebase. This will rebase your work

upon Mrs. Slowrunner’s work and no merge commit will be created. If you work on

a topic branch and would like to sync it with master, simply run git rebase

master. This will reduce pissed off people count too.

Note, however, that rebase rewrites history! This means, that if you have

published your work somewhere, you shouldn’t rebase it, unless you have

warned people that they may expect history rewriting. This is usually refered

to as throw-away branches (for example branch pu of git.git). If you have

published your work, rewritten it and try to publish it again, git push won’t

let you. If you force it to, expect angry people to come to your house with

your local analogue of baseball bats.

Regarding angry people: some workflows require topic branches to be squashed

to a single commit before merging to mainline. This is easy in Git: just use

the --squash option of git merge, and everyone will be happy. If you want to

squash only some of them (for example, make 5 commits out of 20), you can use

aforementioned interactive rebase.

This pretty much concludes this series of Git posts. If you feel that I have left something unveiled, please tell me that! I appreciate all the comments.