Git Is Your Friend not a Foe v1: Distributed

Recently, I’ve been preaching Git to everyone that use the inferior version control software (like SVN or, pardon me, CVS). But somewhy the main obstacle I see in these people is that they are so used to SVN workflow that they don’t see the magnificence and flexibility Git offers.

Many of these people don’t grasp the benefits Git gives, falling back to classic centralized edit–commit-to-server workflow of SVN and whining that “this stupid Git didn’t commit changes in that file; this stupid Git complains about ‘non fast-forward’; this stupid Git ate my kittens; etc.”. I would like to clear something out and introduce them to a better world.

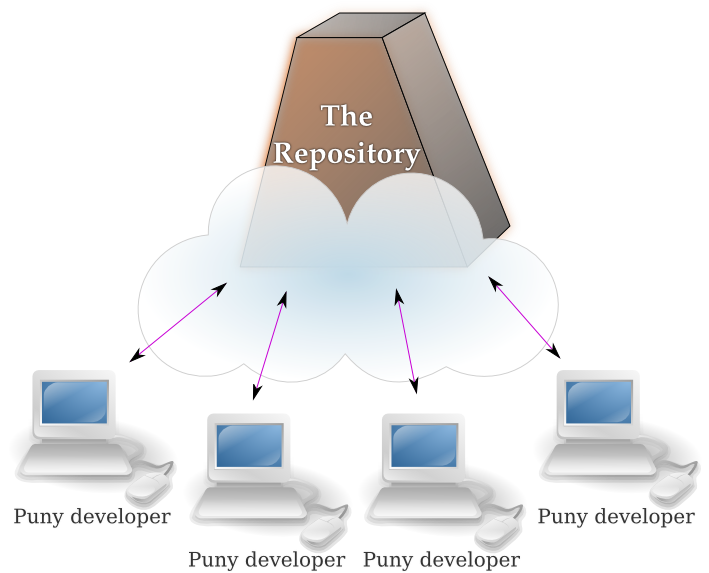

First of all, Git is a distributed version control system. What does that mean? In classic VCS you have a single holy place called The Repository, where all the project’s history is kept. Developers get only the small fraction of information from it: the actual files from the latest revision (termed the “working copy”, which is obviously an exaggeration). Basically, the only thing SVN client is able to do is compare your files with the latest revision and send this diff to the server. In SVN communications are possible only between The Repository and the puny client with the working copy.

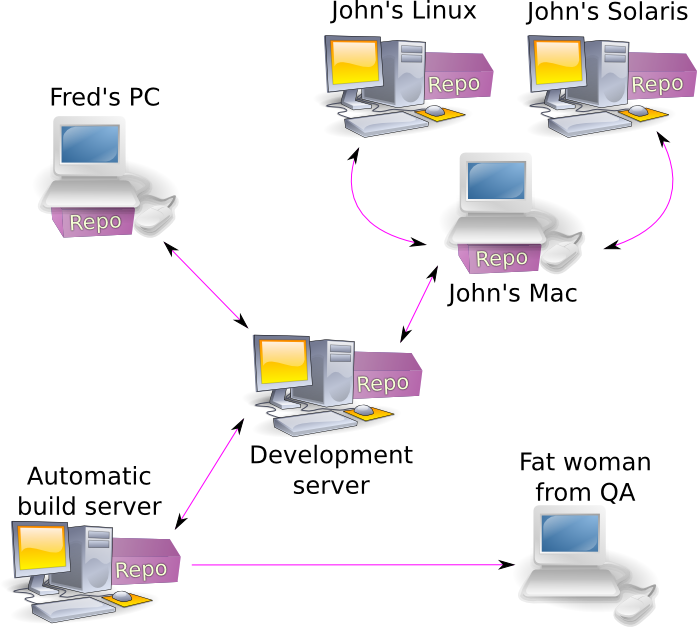

In contrast, Git does not differentiate His Holiness The Repository from mere mortal working copies. Everyone gets a repository of his own. Everyone can do anything they want with it. Each developer can communicate with any other developer. This gives a developer so much freedom, that he often does not get into it, and just simply asks this:

Uhm, an entire development history? With every working copy? Man, that will eat a lot of disk space! And I even can’t imagine how long it will take to checkout that repository!

Well, first, not checkout, but clone. The checkout in Git is a somewhat different operation, and that is a Git club entry fee: you need to lose your centralized VCS habits and get used to new terms and ways. This can be painful at first, but it pays off at the end. You’ll thank me later.

So, back to the repository size. Yes, Git requires you to have the whole repository on your person. Yes, it does increase your project directory size. But Git is extremely efficient in packing stuff, so that increase should not hurt you. In fact, the whole Git repository (with full project history) is known to take less space than an SVN checkout. And SVN’s checkout process is so inefficient, that for most projects Git clone takes less time than SVN checkout.

Okay, now the next question is: what is so cool about having the whole repository along with project files? Well, the most basic advantage is that a developer can do everything without access to the server, i.e.:

- view the revision log starting from the very first commits;

- browse old versions of the project;

- and more importantly, commit his changes.

It is a nice feature being able to browse the history without Internet access for people with slow link, or for people that travel a lot. But being able to commit things without asking anyone’s permission is so important that it’s worth a separate paragraph. Here it goes.

Most software teams recognize the two simple principles that a developer should follow: keep commits atomic and don’t commit bad stuff. The problem is that centralized VCS make these principles incompatible. People just don’t work in a linear discrete fashion, instead they tend to steer between several things: a touch there, a refactor here, an occasional stupid bug fix. In the end you get a working tree with bunch of unrelated, uncommitted and untested changes. In Git you can commit as often as you want because commits are local to your repository, no one sees them except yourself! You can commit total rubbish and test everything later — you can edit every single commit without fear of embarrassment and humiliation. You can find out that the way you started to implement this killer feature everyone wanted is totally wrong and start from scratch — without spoiling the project version history.

The second advantage is that developers can exchange their revisions with each other without the central server. Imagine John having reworked the main loop of nuclear reactor coolant control computer. He doesn’t want to incorporate this change to a live system, so he asks Fred to download the respective changes from his repository and test them on his nuclear plant in less populated area. After not having heard any loud explosions, John knows that at least one plant survived the change.

You can also benefit from this even if you are the only developer. Imagine you have several different computers (for example Mac, Linux x86 and Linux amd64). You have developed something on your Mac box and tested it through and are ready to push this to the main repository. But you may also push it first to your Linux boxes and test it there. In SVN you would have to generate patch, transfer it to the boxes, and apply it. Everything manually. So you most probably wouldn’t bother at all and would discover that nasty bug that occurs only on 64-bit computers only in two month and lose your job.

Finally, the concept of “central repository” may be eliminated altogether. Every developer gets a “public” repository where he keeps the stuff he is not ashamed of and a private repository where he works as he wants. Or a bunch of private repositories. The developers exchange their work by pulling commits from each other’s public repositories. Or they can have a single lead developer, who collects the good commits, and use his repository as a “blessed” repository. The lead developer either watches for changes in other public repositories, or waits for a “merge request”. Merge request is a message (e-mail traditionally) that says something along the lines of “Hey, Sam, I’ve implemented the automatic road crosser for blind one-legged homosexuals, ‘git pull git://acmesoftware.com/~dave/shiny.git crosser’, love, Dave”. Sam copies-and-pastes the command and gets a new branch, tests it, and then pushes to his blessed public repository.

For large projects (for example, Linux) lead developer has several people responsible for specific subsystems (the so called Lieutenants). They collect the small commits from their fellow developers, test them and forward to Linus, who aggregates all the good stuff in his own repository. This ensures that the code is seen by at least one other person, before it gets stored in the repository and completely forgotten.

Also, the nice side-effect of Git being a distributed system is that every repository is essentially a backup of the main repository. It doesn’t mean you should not do backups — you should! — it just means, that in case everything crashes and burns, any developer will provide you with full revision history, not only the recent project files.

There are some more things that confuse novice users, especially branches and staging area. I shall cover them in following posts, stay tuned!