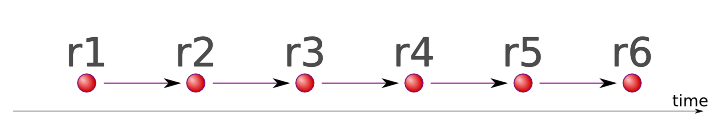

Git Is Your Friend not a Foe v2: Branches

So if you worked with some version control systems for a bit, you’ve probably heard of a concept called branches. It is quite a simple concept: you can perform several development processes in parallel without them interfering with each other. Most projects use branches for experimental features that could set hell loose and for backporting bugfixes to older releases. Subversion and CVS people usually dislike branches, because they involve lots of uninteresting and painful work that they don’t want to do. That is easily explained by the way branches are implemented there.

As you might know, branches in SVN are implemented in a very interesting fashion. They are not, in fact, implemented at all. SVN branch is just a folder, which is created when a branch is started. If you want to merge it back, you need to remember the revision number, when you created the branch, and use that magical number in a complex “svn merge” command. But still, SVN project history remains a straight line.

What’s wrong with this way of interpreting the branch concept? Nothing. It’s completely fine, if you don’t want to work with branches. And you should want to work with branches, because they are actually awesome! Especially if implemented as in Git.

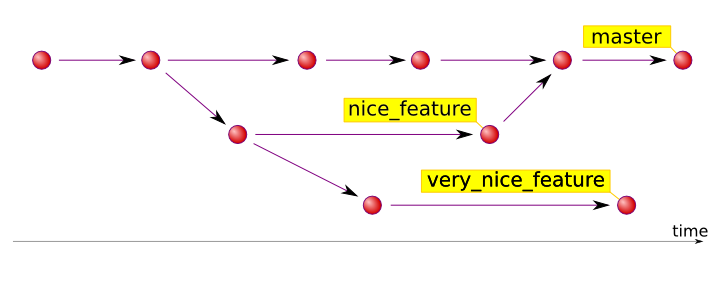

Instead of SVN-y linear development history, Git’s commit history is a more complex structure: each commit can have multiple parents and multiple children. In computer science this is called a Directed Acyclic Graph (and if this rings any bells you may want to read Tv’s article Git for Computer Scientists). In practice that means that you are not restricted to developing upon the latest revision in project’s history. Instead, you can take any existing commits and start creating commits off it. If you want to merge them, you create a commit that is a child of two commits (such children are called merge commits).

This way you get a graph with several commits with no children (let’s call

them branch heads for now). Every commit has a reference to its parent. So if

we take the branch head, we can trace back the project history to the very

beginning. This is why the Git branch is simply a reference to its head (you

can go ahead and look into the files in .git/refs/heads directory of any of

your Git repositories).

Most of the time you will have a checked-out branch (the special reference

HEAD points to the current branch, see .git/HEAD for example). When you commit

something, your commits are attached to it and the branch reference is moved

to the new commit. Simple. But sometimes your HEAD may point to something

other than a branch head (for example, when you checkout an older revision by

its ID or tag). This is called a detached head. It is a very simple,

important and confusing situation. There’s nothing wrong about it, but it

hides a peril: if you commit to a detached head, Git creates a new commit and

attaches it to the current commit, forming a branch. But this branch has no

name! It will just grow sideways as a normal branch without a name. Here’s

what’s wrong with it:

- it is confusing, because commits do not go to master, or whatever branch you had checked out before;

- if you check out another branch, you won’t be able to return to this branch by its name, it simply doesn’t have any.

Note, that Git won’t let you lose data easily and won’t force you to do unneeded work. Let me tell you what to do in case you have committed to a detached head. Suppose you created just one single commit to a detached head and now just sit and look at it. You have two options:

- create a new branch with the current commit as a head: `git branch

`, - attach the new commit to another branch (suppose it is branch master):

remember the ID of the new commit, checkout the required branch (

git checkout master), cherry-pick your commit to it (git cherry-pick *id*).

If you find yourself in the second situation (you’ve just committed to a

detached head, checked out another branch and don’t remember the commit id),

you may use Git’s reflog (git reflog, or git log -g). This will list the

history of your HEAD (checkouts, commits and the such), where you can take

commit ID and use it wisely.

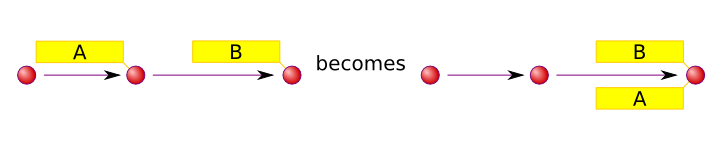

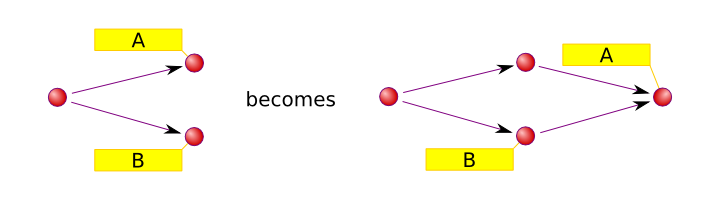

Merging is an important part of Git workflow. You will, in fact, do merges frequently even if you don’t use branches other than master, provided you use more than one repository. That is because master of one repository and master of another repository are, in general, different branches. So when you do push or pull to/from another repository you do a merge. Git differentiates two merge types (suppose you attempt to merge branch B into branch A):

- fast-forward merge. This happens when B is a direct descendant of A.

This is resolved trivially: Git simply moves reference A to point to B,

- non fast-forward merge. This covers all the remaining cases, and

requires a merge commit to be created (merge commit is a commit with at

least two parents).

This differentiation is important because the fast-forward merge can be performed automatically without human intervention. That’s why this is the only merge possible during Git push. The non fast-forward merge may result in edit conflicts (the situation when two lines of development changed the same line of the same file differently), so a human intervention may be required. This is what is meant by a (not immediately clear) git-push message “remote rejected: non fast-forward”: sorry, I can’t push your modifications, because remote branch has diverged, please resolve this manually. Most often this occurs when another developer managed to push his changes first. In this case just run “git pull”, resolve conflicts (if any), then run “git push”. Less often this occurs when a remote branch has been changed completely (for example, branch pu of Git Git repository is changed very frequently and is not supposed to be developed upon). This means that either you or the remote repository owner screwed up, so you’d better talk to each other. Sometimes this occurs when you try to push to a completely unrelated repository. So just be careful there.

I should note here, that the --force option to git-push along with +refspec

notation is not going to solve your problems automagically. It will simply

destroy the remote history, replacing with your own. So you should never

use it, unless you know exactly what you are doing.

Next up: rebasing and staging area.