Git Is Your Friend not a Foe v3: Refs and Index

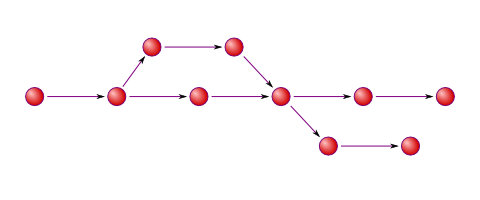

Let’s take a walk along Git repository structure. The central square is Git

Object Database. Objects reference each other by 160-bit unique IDs with a

certain semantics (for example, commit-object references its parent commit(s)

and the tree that corresponds to project’s root directory; tree-object

references blob-objects that correspond to file content and tree-objects that

correspond to subdirectories; etc., see gittutorial-2(7) for details). For

the sake of simplicity, let’s forget about trees and blobs for now, and look at

commits only.

We now have a bunch of commits that know who were their parents. We can trace

history from any given commit back to the very beginning. But how do we know

what is the current state of things? What was the latest commit in the

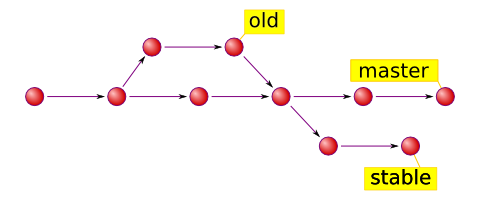

history? To answer that let’s look at Git refs (short for references). They

are basically named references for Git commits. There are two major types of

refs: tags and heads. Tags are fixed references that mark a specific point

in history, for example v2.6.29. On the contrary, heads are

always moved to reflect the current position of project development.

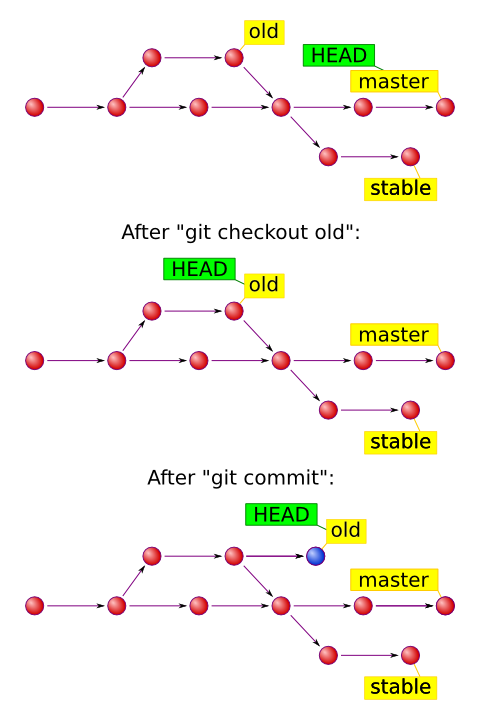

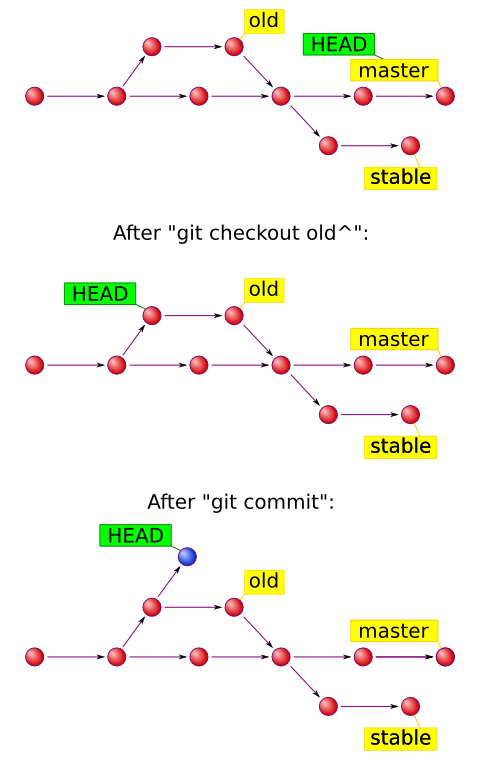

Now we know what is happening in the project. But to know what is happening

right here, right now there is a special reference called HEAD. It serves two

major purposes: it tells Git which commit to take files from when you checkout

and it tells Git where to put new commits when you commit. When you run

git checkout <ref> it points HEAD to the ref you’ve designated

and extracts files from it. When you run git commit it creates a

new commit object, which becomes a child of current HEAD. Normally HEAD points

to one of the heads, so everything works out just fine.

But if you checkout a specific commit instead of a branch, your HEAD starts pointing at this commit. This is referred to as detached head and you may be told that you are not on a branch (git branch says “(no branch)”). This is perfectly fine, but if you commit anything to it, your commits won’t have a known ref, so if you checkout another branch, you can lose them.

Having said about committing, can’t help stopping by the process of committing

itself. You may already know that the Git’s “add” operation differs from

almost every other VCS in that you have to “add” not only files that are not

yet known to Git, but also files that you have just modified. This is because

Git takes content for next commit not from your working copy, but from a

special temporary area, called index. This allows finer control over what

is going to be committed. You can not only exclude some files from commit, you

can exclude even certain pieces of files from commit (try git add -i). This

helps developers stick to atomic commits principle.

And if you have inhuman ability of creating only perfect committs and need

stupid VCS only to obey your orders, then you can just use option -a for

git-commit. And I envy you.

Another special kind of refs are remotes. Whenever you run git

fetch, it asks the remote repository, what heads and tags does it have,

downloads missing objects (if any) and stores remote refs under refs/remotes

prefix. The remote heads are displayed if you run git branch -r.

Some of your branches (notably master) may be what is called tracking

branches. That means that a certain branch “tracks” its remote counterpart.

Physically that means that when you run git pull on that branch,

the corresponding remote branch gets automatically merged into your local

branch. Fairly recent versions of Git set up tracking automatically when you

checkout a remote branch (for example, git checkout -b stable

origin/stable). Note, however, that sometimes it’s better to rebase

instead of merge.

But that’s a whole new story…